Imagine for a moment, the process of therapy. It is a give and take where the participant wants change to occur, both in themselves, and in how they interact in the world. Something in the past has not gone as right as they’d like, and this process is meant to help them explore a better path ahead. Imagine also the clinician is in the room with them, listening intently as they speak about their experiences and works on the formulation of hypotheses to explain the client’s behavior both in and outside of therapy. In the therapy setting, even listening to these stories and relations of what happened in the past, the clinician is still limited in their full understanding of the information and experience. They do not have enough information, even from detailed stories, to come to a full conclusion.

In an experimental setting, a behavior analyst might find ways to mimic the natural environment, and contrive similar situations and stimuli for the client to engage with in order to get more information. They may try to manipulate the environment as best they could to see how the client responds to simulated contingencies. It could be roleplay. Something close to the original but not exactly that, something controlled with just enough of the original event to elicit similar behavior. It might even come close, and shed more details on what factors maintain certain behavior patterns. Progress. You would not want exposure to something that was expressed in confidence and trust, especially something fearful or aversive, to be presented without preparation or complete consent. It would be carefully chosen, described, and all features of the design and presentation would be agreed on. Progress would grow from mutually prepared steps.

But there is also a part that is somewhat subjective on the part of the clinician. Even if they did a great deal of functional analytic work on both indirect assessments, through interview, and direct assessments, with an experimental scenario, an interpretation is necessary. In fact, it’s owed to the client. They want to have an explanatory system for what is going on, and what can be done to make things better. It needs to tie in and make sense with what they have told, and the experiences they related. It is the duty of the clinician to be as careful as possible with the information they have received, and made the best hypotheses, not out of thin air, but from research and the functional and relational frameworks that could be understood from it.

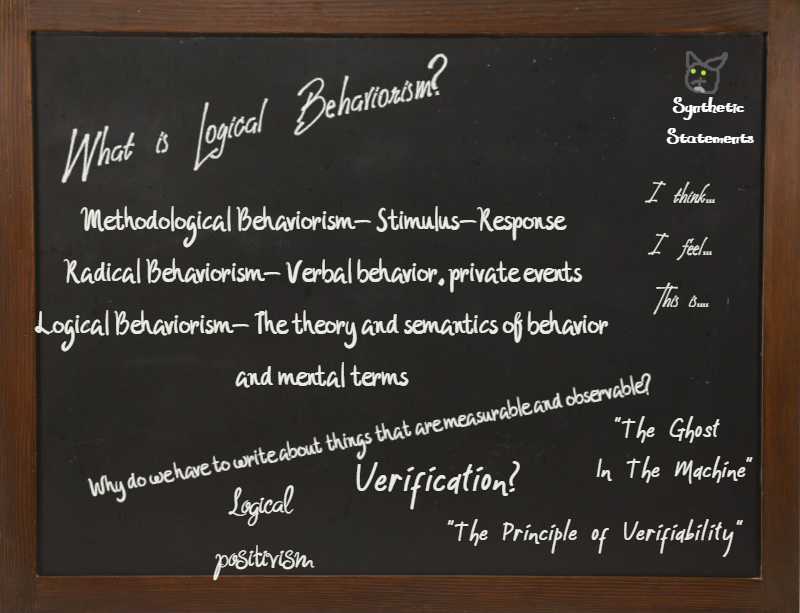

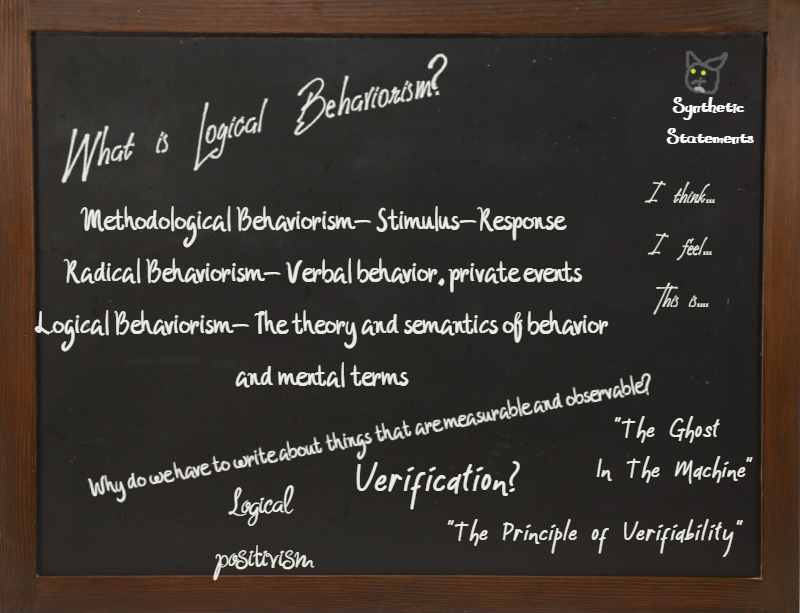

Interpretation has been around a very long time in psychology. From the old Freudian psychoanalytic methods, interpretation was a great deal of the process. A story, or memory, or dream would be related to the psychoanalyst, and from that there would be an interpretation based on what the analyst saw in the subconscious of that individual. Sometimes it was helpful. Sometimes it was not. Since then, the field has been split on those specific methods of interpretation. In behavior analysis, those intuitive leaps have largely been set aside for more concrete environmental events and not hypothetical subconscious features. A person’s environment, including all the people and experiences they have been affected by, are what behavior analysis largely deals in. There is a focus on the outer world, the experiences that shaped an individual, that is said to have more scientific bearing than trying to guess at a hypothetical construct of subconscious from another person.

In behavior analysis, we prefer to look at the longer behavioral patterns as having more predictability to them. When we see a long term pattern of behavior, it makes the process of contriving changes in the person’s environment more straight forward. We can introduce a new variable and see the change. If a person’s behavior is erratic over a long period, with a great deal of variability, it makes it all the more challenging to know what new change has any effect, if at all. Stable behavioral traits, and patterns, give something to base interpretation of results off of. It’s a baseline. Using a baseline is also helpful in interpretations as well. Think of it as the start of a story. The baseline is the opening of the therapeutic story. Imagine a 10 chapter story. This is chapter 1.

Next comes the data. In behavior analysis, it is the measurable and observable which is trusted most, but even someone relating a story of a past experience can be measured and observed when we make the features of that related information salient enough to test. If someone says they have trouble ditching cigarettes, we could ask how many they have a day, determine a baseline rate, and go from there. Changing variables onward, based on that daily average, can give us information which is observable and measurable (fewer cigarettes smoked). Stepping away from that example, let’s imagine the behavior is more anxiety based, perhaps avoidance of certain situations, people, or information. While we probe on past experiences we may learn something to base our treatment on. Also, during this period of probing and hypothesizing, there may be more uncovered. Information that was not salient before might pop up in the information related by the client.

In certain psychological traditions, this is the end. Catharsis is what it was called. Information that was deeply buried, eliciting a strong emotional response in therapy, was seen as curative in itself (that will be another topic in the next post). To many, it does feel that way. It feels like a relief. In behavior analysis, however, we try to take it a step further. The uncovering of a past trigger, or antecedent, is valuable. Absolutely. But then we ask, does that change the behavior we are targeting now? Does that expression in therapy, by itself, make the avoidance diminish? It may, but in many cases, it takes the behavior of the client afterwards to make lasting change and growth. But, we have causal information. Our hypothesis is stronger. We can use that in our framework for behavioral change and success. That is the next step in the therapeutic interpretation, the story, and let’s call that chapter’s 2-5. We have now determined a pattern, and have started an intervention to it.

Next, comes analysis. Imagine over the course of the following weeks we see a broader lasting change. Let’s say that when the new therapeutic change was put in place, and the behavior we wanted to see drop actually dropped in the long term, we can assume there is a degree of control there. The therapeutic technique seems to work. Now, we can’t say it works for everyone. We can’t say it works all the time. We can’t even say that if a bad day hits with all the old triggers for the maladaptive behavior, that it would not return. What we can interpret and say is that, given the situations we have tried here, we have a level of control that can be seen, and hopefully, the client has been happy with. It delivers the wind down of the process, which may lead to even more changes and tweaks along the way. There may be several more adjustments, different treatment options, different environmental changes that stem from. Let’s call this chapter 6-7. The story is not over.

Our interpretation here is verbal. It is a narrative, a story, an explanation of complex behavioral, neurological, and environmental change that is summed up in a way that makes sense to us. The analyst and the client can agree on what the important factors are, and the change is spoken of in a way that the client can understand. If the clinician values the use of an interpretation, they won’t over use scientific jargon if it’s unnecessary. A word like reinforcement might be key, but it would be used for the purpose of relating a specific useful piece of information within the interpretation. The interpretation isn’t magical either. It doesn’t solve the situation in itself. It is chapters 8-9. It gives an account of a behavioral pattern that has been explored, and changed, but without the false promise of that change lasting forever. When it is related to the client, they may understand how their past experiences, their environment and reinforcement or punishment history affected them, and with the intervention, changed in a better direction. The interpretation can be valuable to them to that degree. It codifies a type of behavioral transformation, a change, a growth, a learning experience. But we have to be very clear that this interpretation is not final, or complete. When looking at the lifespan of an individual, behavior is what they do from the start of life to the very end.

Chapter 10 doesn’t come until the end of a lifetime. There is no way to conceptualize the finality of a person’s behavior without the whole story. This is largely outside the scope of therapeutic interpretation, but is important to it. It is always ahead, which means that the therapeutic interpretation maybe complete in the short term, but will necessarily never be in the long.

Thoughts? Questions? Comments? Leave them below.

References:

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied Behavior Analysis. Pearson Education Limited.

Dougher, M. J. (2000). Clinical behavior analysis. Context Press.

Madden, G. J., & Dube, W. V. (2013). Apa Handbook of Behavior Analysis. American Psychological Association.

Image Credits: pexels.com